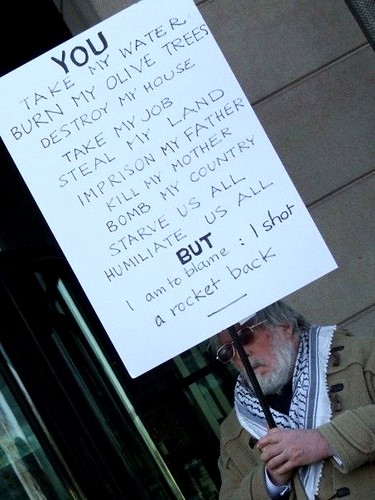

From Haaretz, we find that a secret database has been revealed which details the extent of illegal Israeli settlements and how they were created and nurtured with the support of successive Israeli governments.

Just four years ago, the defense establishment decided to carry out a seemingly elementary task: establish a comprehensive database on the settlements. Brigadier General (res.) Baruch Spiegel, aide to then defense minister Shaul Mofaz, was put in charge of the project. For over two years, Spiegel and his staff, who all signed a special confidentiality agreement, went about systematically collecting data, primarily from the Civil Administration.

One of the main reasons for this effort was the need to have credible and accessible information at the ready to contend with legal actions brought by Palestinian residents, human rights organizations and leftist movements challenging the legality of construction in the settlements and the use of private lands to establish or expand them. The painstakingly amassed data was labeled political dynamite.

The defense establishment, led by Defense Minister Ehud Barak, steadfastly refused to publicize the figures, arguing, for one thing, that publication could endanger state security or harm Israel’s foreign relations. Someone who is liable to be particularly interested in the data collected by Spiegel is George Mitchell, President Barack Obama’s special envoy to the Middle East, who came to Israel this week for his first visit since his appointment. It was Mitchell who authored the 2001 report that led to the formulation of the road map, which established a parallel between halting terror and halting construction in the settlements.

The official database, the most comprehensive one of its kind ever compiled in Israel about the territories, was recently obtained by Haaretz. Here, for the first time, information the state has been hiding for years is revealed. An analysis of the data reveals that, in the vast majority of the settlements – about 75 percent – construction, sometimes on a large scale, has been carried out without the appropriate permits or contrary to the permits that were issued. The database also shows that, in more than 30 settlements, extensive construction of buildings and infrastructure (roads, schools, synagogues, yeshivas and even police

stations) has been carried out on private lands belonging to Palestinian West Bank residents.

Click here to view the secret Defense Ministry database on illegal construction in the territories. It should be noted that the information is given in Hebrew

The data, it should be stressed, do not refer only to the illegal outposts (information about which was included in the well-known report authored by attorney Talia Sasson and published in March 2005), but to the very heart of the settlement enterprise. Among them are veteran ideological settlements like Alon Shvut (established in 1970 and currently home to 3,291 residents, including Rabbi Yoel Bin Nun); Ofra (established in 1975, home to 2,708 residents, including

former Yesha Council spokesman Yehoshua Mor Yosef and media personalities Uri Elitzur and Hagai Segal); and Beit El (established in 1977, population 5,308, including Hagai Ben-Artzi, brother of Sara Netanyahu). Also included are large settlements founded primarily for economic motives, such as the city of Modi’in Illit (established in 1990 and now home to 36,282 people), or Givat Ze’ev outside Jerusalem (founded in 1983, population 11,139), and smaller settlements such as Nokdim near Herodion (established in 1982, population 851, including MK Avigdor Lieberman).

The information contained in the database does not conform to the state’s official position, as presented, for instance, on the Foreign Ministry Web site, which states: “Israel’s actions relating to the use and allocation of land under its administration are all taken with strict regard to the rules and norms of international law – Israel does not requisition private land for the establishment of settlements.” Since in many of the settlements, it was the government itself, primarily through the Ministry of Construction and Housing, that was responsible for construction, and since many of the building violations involve infrastructure, roads, public buildings and so on, the official data also demonstrate government responsibility for the unrestrained planning and lack of enforcement of regulations in the territories. The extent of building violations also attests to the poor functioning of

the Civil Administration, the body in charge of permits and supervision of construction in the territories.

According to the 2008 data from the Central Bureau of Statistics, approximately 290,000 Jews live in the 120 official settlements and dozens of outposts established throughout the West Bank over the past 41 years.

“Nothing was done in hiding,” says Pinchas Wallerstein, director-general of the Yesha Council of settlements and a leading figure in the settlement project. “I’m not familiar with any [building] plans that were not the initiative of the Israeli government.” He says that if the owners of private land upon which settlements are built were to complain and the court were to accept their complaint, then the structures would have to be moved somewhere else. “This has been the Yesha

Council’s position for the past years,” he says.

You’d never know it from touring several of the settlements in which massive construction has taken place on private Palestinian lands. Entire neighborhoods built without permits or on private lands are inseparable parts of the settlements. The sense of dissonance only intensifies when you find that municipal offices, police and fire stations were also built upon and currently operate on lands that belong to Palestinians.

On Misheknot Haro’im Street in the Kochav Yaakov settlement, a young mother is carrying her two children home. “I’ve lived here for six years,” she says, sounding surprised when told that her entire neighborhood was built upon private Palestinian land. “I know that there’s some small area in the community that is in dispute, but I never heard that this is private land.” Would she have built her home on this land had she known this from the start? “No,” she answers. “I wouldn’t have kicked anyone out of his home.”

Not far away, at the settlement’s large and unkempt trailer site, which is also built on private land, a young newlywed couple is walking to the bus stop: 21-year-old Aharon and his 19-year-old wife, Elisheva. They speak nearly perfect Hebrew despite having grown up in the United States and having settled permanently in Israel just a few months ago, after Aharon completed his army service in the ultra-Orthodox Nahal unit. Now he is studying computers at Machon Lev in Jerusalem. Asked why they chose to live here of all places, they list three reasons: It’s close to Jerusalem, it’s cheap and it’s in the territories. In that order.

The couple pay their rent, NIS 550 a month, to the settlement secretariat. As new immigrants, they are still exempt from having to pay the arnona municipal tax. Aharon doesn’t look upset when he hears that his trailer sits on private land. It doesn’t really interest him. “I don’t care what the state says, the Torah says that the entire Land of Israel is ours.” And what will happen if they’re told to move to non-private land? “We’ll move,” he says without hesitation.

A complicated problem

Even today, more than two years after concluding his official role, Baruch Spiegel remains loyal to the establishment. In a conversation, he notes several times that he signed a confidentiality agreement and so is not willing to go into the details of the work for which he was responsible. He was appointed by Shaul Mofaz to handle several issues about which Israel had given a commitment to the United States, including improving conditions for Palestinians whose lives were adversely affected by the separation fence, and supervision of IDF soldiers at the checkpoints.

Two years ago, Haaretz reporter Amos Harel revealed that the main task given Spiegel was to establish and maintain an up-to-date database on the settlement enterprise. This was after it became apparent that the United States, as well as Peace Now’s settlement monitoring team, was in possession of much more precise information about settlement construction than was the defense establishment, which up to then had relied mostly on information collected by Civil Administration inspectors. The old database had many gaps in it, which was largely a consequence of the establishment preferring not to know exactly what was going on in this area.

Spiegel’s database contains written information backed up by aerial photos and layers of GIS (Geographic Information Systems) data that includes information on the status of the land and the official boundaries of each settlement. “The work took two and a half years,” says Spiegel. “It was done in order to check the status of the settlements and the outposts and to achieve the greatest possible accuracy in terms of the database: the land status, the legal status, the sector boundaries, the city building plan, government decisions, lands whose ownership is unclear. It was full-time, professional work done with a professional team of legal experts, planning people, GIS experts. And I hope that this work continues, because it

is very vital. One has to know what’s going on there and make decisions accordingly.”

Who is keeping track of all of this now?

“I suppose it’s the Civil Administration.”

Why was there no database like this before your appointment?

“I don’t know how much of a focus there was on doing it.”

Why do you think the state is not publicizing the data?

“It’s a sensitive and complex subject and there are all kinds of considerations, political and security-related. There were questions about the public’s right to know, the freedom of information law. You should ask the officials in charge.”

What are the sensitive matters?

“It’s no secret that there are violations, that there are problems having to do with land. It’s a complicated problem.”

Is there also a problem for the country’s image?

“I didn’t concern myself with image. I was engaged in Sisyphean work to ensure that, first of all, they’ll know what exists and what’s legal and what’s not legal and what the degree of illegality is, whether it involves the takeover of private Palestinian land or something in the process of obtaining proper building permits. Our job was to do the meticulous work of going over all the settlements and outposts that existed then – We found what we found and passed it on.”

Do you think that this information should be published?

“I think they’ve already decided to publish the simpler part, concerning areas of jurisdiction. There are things that are more sensitive. It’s no secret that there are problems, and it’s impossible to do something illegal and say that it’s legal. I can’t elaborate, because I’m still bound to maintain confidentiality.”

Dror Etkes, formerly the coordinator of Peace Now’s settlement monitoring project and currently director of the Land Advocacy Project for the Yesh Din organization, says, “The government’s ongoing refusal to reveal this material on the pretext of security reasons is yet another striking example of the way in which the state exploits its authority to reduce the information at the citizens’ disposal, when they wish to formulate intelligent positions based on facts rather than lies and half-truths.”

Following the initial exposure of the material, the Movement for Freedom of Information and Peace Now requested that the Defense Ministry publish the database, in accordance with the Freedom of Information law. The Defense Ministry refused. “This is a computerized database that includes detailed information, in different cross-sections, regarding the Jewish settlements in Judea and Samaria,” the Defense Ministry said in response. “The material was collected by the defense establishment for its purposes and includes sensitive information. The ministry was asked to allow a review of the material in accordance with the Freedom of Information law, and after consideration of the request, decided not to hand over the material. The matter is pending and is the subject of a petition before the Administrative Affairs Court in Tel Aviv.”

Ofra, Elon Moreh, Beit El

The database surveys settlement after settlement alphabetically. For each entry, it notes the source of the settlement’s name and the form of settlement there (urban community, local council, moshav, kibbutz, etc.); its organizational affiliation (Herut, Amana, Takam, etc.), the number of inhabitants, pertinent government decisions, the official bodies to which the land was given, the status of the land upon which the settlement was built (state land, private Palestinian or Jewish land, etc.), a survey of the illegal outposts built in proximity to the settlement and to what extent the valid building plans have been executed. Beneath each entry, highlighted in red, is information on the extent of construction that has been carried out without permission and its exact location in the settlement.

Among all the revelations in the official data, it’s quite fascinating to see what was written about Ofra, a veteran Gush Emunim settlement. According to a recent B’tselem report, most of the settlement’s developed area sits on private Palestinian land and therefore falls into the category of an illegal outpost that is supposed to be evacuated. The Yesha Council responded to the B’tselem report, saying that the “facts” in it are “completely baseless and designed to present a false picture. The inhabitants of Ofra are careful to respect the rights of the Arab landowners, with whom they reached an agreement regarding the construction of the neighborhoods as well as an agreement that enables the private landowners to continue to work their lands.”

But the information in the database about Ofra leaves no room for doubt: “The settlement does not conform to valid building plans. A majority of the construction in the community is on registered private lands without any legal basis whatsoever and no possibility of [converting the land to non-private use].” The database also gives a detailed description of where construction was carried out in Ofra without permits: “The original part of the settlement: [this includes] more than 200 permanent residential structures, agricultural structures, public structures, lots, roads and orchards in the old section of the settlement (in regard to which Plan 221 was submitted, but not advanced due to a problem of ownership).” After mentioning 75 trailers and temporary shelters in two groups within the old settlement, the database mentions the Ramat Zvi neighborhood, south of the original settlement: “There are about 200 permanent structures as well as lots being developed for additional permanent construction, all trespassing on private lands.” Yesha Council chairman Danny Dayan responds: “I am not familiar with that data.”

Another place where the data reveals illegal construction is Elon Moreh, one of the most famous settlements in the territories. In June 1979, several residents of the village of Rujib, southeast of Nablus, petitioned the High Court, asking it to annul the appropriation order for 5,000 dunams of land in their possession, that had been designated for the construction of the settlement. In court, the government argued, as it did regularly at the time, that the construction of the settlement was required for military needs, and therefore the appropriation orders were legal. But in a statement on behalf of the petitioners, former chief of staff Haim Bar-Lev asserted that, “In my best professional judgment, Elon Moreh does not contribute to Israel’s security.”

The High Court, relying on this statement and the statements of the original core group of settlers of Elon Moreh, who also argued that this was not a temporary settlement established for security purposes, but a permanent settlement, instructed the IDF to evacuate the settlement and return the lands to their owners. The immediate consequence of the ruling was to find an alternative site for construction of the settlement, on lands previously defined as “state lands.” Following this ruling, Israel stopped officially using military injunctions in the territories for the purpose of establishing new settlements.

The lands that were originally taken for the purpose of building Elon Moreh were returned to their Palestinian owners, but according to the database, also in the new site where the settlement was built, called Har Kabir, “most of the construction was done without approved, detailed plans, and some of the construction involved trespassing on private lands. As for the state lands in the settlement, a detailed plan, no. 107/1, was prepared and published on 16/7/99, but has yet to go into effect.”

The Shomron regional council, which includes Elon Moreh, said in response: “All the neighborhoods in the settlement were planned, and some were also built, by the State of Israel through the Housing Ministry. The residents of Elon Moreh did not trespass at all and any allegation of this kind is also false. The State of Israel is tasked with promoting and approving the building plans in the settlement, as everywhere else in the country, and as for the plans that supposedly have yet to receive final validity, just like many other communities throughout Israel, where the processes continue for decades, this does not delay the plans, even if the planning is not complete or being done in tandem.”

Beit El, another veteran settlement, was also, according to the database, established “on private lands seized for military purposes (In fact, the settlement was expanded on private lands, by means of trespassing in the northern section of the settlement) and on state lands that were appropriated during the Jordanian period (the Maoz Tzur neighborhood in the south of the settlement).”

According to the official data, construction in Beit El in the absence of approved plans includes the council office buildings and the “northern neighborhood (Beit El Bet) that was built for the most part on private lands. The neighborhood comprises widespread construction, public buildings and new ring roads (about 80 permanent buildings and trailers); the northeastern neighborhood (between Jabal Artis and the old part of the settlement) includes about 20 permanent residential buildings, public buildings (including a school building), 40 trailers and an industrial zone (10 industrial buildings). The entire compound is located on private land and has no plan attached.”

Moshe Rosenbaum, head of the Beit El local council, responds: “Unfortunately, you are cooperating with the worst of Israel’s enemies and causing tremendous damage to the whole country.”

‘One giant bluff’

Ron Nahman, mayor of Ariel, was re-elected to a sixth term in the last elections. Nahman is a long-time resident of the territories and runs a fascinating heterogeneous city. Between a visit to the trailer site where evacuees from Netzarim are housed and a stop at a shop that sells pork and other non-kosher products, mostly to the city’s large Russian population, Nahman complains about the halting of construction in his city and about his battles with the Civil

Administration over every building permit.

Ariel College, Nahman’s pride and joy, is also mentioned in the database: “The area upon which Ariel College was built was not regulated in terms of planning.” It further explains that the institution sits on two separate plots and the new plan has not yet been discussed. Nahman confirms this, but says the planning issue was recently resolved.

When told that dozens of settlements include construction on private lands, he is not surprised. “That’s possible,” he says. The fact that in three-quarters of the settlements, there has been construction that deviates from the approved plans doesn’t surprise him either. “All the complaints should be directed at the government, not at us,” he says. “As for the small and communal settlements, they were planned by the Housing Ministry’s Rural Building Administration. The larger communities are planned by the ministry’s district offices. It’s all the government. Sometimes the Housing Ministry is responsible for budgetary construction, which is construction out of the state budget. In the Build Your Own Home program, the state pays a share of the development costs and the rest is paid for by the individual. All of these things are one giant bluff. Am I the one who planned the settlements? It was Sharon, Peres, Rabin, Golda, Dayan.”

The database provides information attesting to a failure to adhere to planning guidelines in the territories. For example, an attempt to determine the status of the land of the Argaman settlement in the Jordan Rift Valley found that “the community was apparently established on the basis of an appropriation order from 1968 that was not located.” About Mevo Horon, the database says: “The settlement was built without a government decision on lands that are mostly private within a closed area in the Latrun enclave (Area Yod). There was an allocation

for the area to the WZO from 1995, which was issued as in a deviation from authority, apparently on the basis of a political directive.” In the Tekoa settlement, trailers were leased to the IDF “and installed contrary to the area’s designation according to a detailed plan? and some also deviate from the boundaries of the plan.”

Most of the territories of the West Bank have not been annexed to Israel, and therefore regulations for the establishment and construction of communities there differ from those that apply within Israel proper. The Sasson report, which dealt with the illegal outposts, was based in part on data collected by Spiegel, and listed the criteria necessary for the establishment of a new settlement in the territories:

1. The Israeli government issued a decision to establish the settlement

2. The settlement has a defined jurisdictional area

3. The settlement has a detailed, approved outline plan

4. The settlement lies on state land or on land that was purchased by Israelis and registered under their name in the Land Registry.

According to the database, the state gave the World Zionist Organization (WZO) and/or the Construction and Housing Ministry authorization to plan and build on most of the territories upon which the settlements were constructed. These bodies allocated the land to those who eventually carried out the actual construction of the settlement: Sometimes it was the Settlement Division of the WZO and other times it was the Construction and Housing Ministry itself, sometimes through the Rural Building Administration. In several cases, settlements were built by Amana, the Gush Emunim settlement arm. Another body cited in the database as having received allocations and being responsible for construction in some of the settlements is Gush Emunim’s Settler National Fund.

Talmud Torah

@Text: Regular schools and religious schools (Talmudei Torah) have also been built on Palestinian lands. According to the database, in the southern part of the Ateret settlement, “15 structures were built outside of state lands, which are used for the Kinor David yeshiva. There are also new ring roads and a special security area that is illegal.” Kinor David is the name of a “yeshiva high school with a musical framework.” The sign at the entrance says the yeshiva was built by the Amana settlement movement, the Mateh Binyamin local council and the

WZO settlement division.

The data regarding Michmash also make it very clear that part of the settlement was built on “private lands via trespassing.” For example, “In the center of the settlement (near the main entrance) is a trailer neighborhood that serves as a Talmud Torah and other buildings (30 trailers) on private land.”

On a winter’s afternoon, a bunch of young children were playing there, one of them wearing a shirt printed with the words “We won’t forget and we won’t

forgive.” There were no teachers in sight. A young woman in slacks, taking her baby to the doctor, stopped for a moment to chat. She moved here from Ashkelon because her husband’s parents are among the settlement’s founders. When her son is old enough for preschool, she won’t send him to the Talmud Torah. Not because it sits on private land, but just because that’s not the type of education she wants for him. “I don’t think there’s been construction on private land here,” she said. “I don’t think there ought to be, either.”

In the Psagot settlement, where there has also been a lot of construction on private land, it’s easy to discern the terracing style typical of Palestinian agriculture in the region. According to the database, in Psagot there are “agricultural structures (a winery and storehouses) to the east of the settlement, close to the grapevines cultivated by the settlement by trespassing.” During a visit here, the winery was abandoned. Its owner, Yaakov Berg, acquired land from the Israel Lands Administration near the Migron outpost and a new winery and regional visitors’ center is currently under construction there.

“The vineyards are located in Psagot,” says Berg, who is busy with the preparations for the new site. From the unfinished observation deck one can see an enormous quarry in the mountains across the way. “If I built a bathroom here without permission from the Civil Administration, within 15 minutes, a helicopter would be here and I’d be told that it was prohibited,” Berg complains. “And right here there’s an illegal Palestinian quarry that continues to operate.”

The politicians did it

Kobi Bleich, spokesperson for the Ministry of Construction and Housing: “The ministry participates in subsidizing the development costs of settlements in Priority Area A, in accordance with decisions of the Israeli government. Development works are carried out by the regional councils, and only after the ministry has ascertained that the new neighborhood is located within an approved city plan. This applies throughout Israel as well as in the areas over the Green Line. Let me emphasize that the ministry’s employees are charged with implementing the policies of the Israeli government. All of the actions in the past were

done solely in keeping with the decisions of the political echelon.”

Danny Poleg, spokesperson for the Judea and Samaria district of the Israel Police: “The issue of the construction of police facilities is the responsibility of the Ministry of Internal Security, so any questions should be addressed to them.”

The Internal Security Ministry spokesman responds: “And for construction by the police is allocated by the Israel Lands Administration in coordination with the Internal Security Ministry. There is no police station in Modi’in Ilit, but a rapid response post for the local residents on land allocated by the local authority. The land in Givat Ze’ev was allocated by the local council and the police station is located within the municipality. The road to the police headquarters was built by the Housing and Construction ministry and is maintained by the local council.”

Avi Roeh, head of the Mateh Binyamin regional council (whose jurisdiction includes the settlements of Ofra, Kochav Yaakov, Ateret, Ma’aleh Michmash and Psagot): “The Mateh Binyamin regional council, like the neighboring councils in Judea and Samaria, is coping with political decisions regarding the manner of the the communities’ expansion. However, this does not remove the need for proper planning procedures in order to expand the settlements in an orderly manner and in accordance with the law.”

For its response, the WZO sent a thick booklet, a copy of which was previously sent to attorney Talia Sasson in response to her report. “Settlement in Judea and Samaria, as in Israel, has been accompanied by the preparation of regional master plans,” says the booklet. “Steering committees from various government ministries, the Civil Administration and the municipal authorities were involved in the preparation of these plans? The (settlement) department worked solely on lands that were given to it by contract from the authorities in the Civil Administration and all the lands that were allocated to it by contract were properly

allocated.”

The Civil Administration, which was first asked for a response regarding the database more than a month ago, has yet to reply.