As Arthur Koestler wrote “Here was one nation promising another nation the land of a third nation.”

As Arthur Koestler wrote “Here was one nation promising another nation the land of a third nation.”

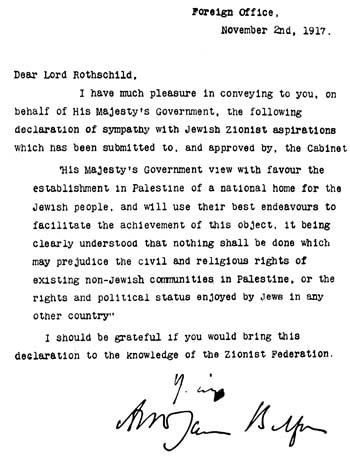

The Balfour Declaration, a shonky deal prepared through British and Zionist intrigue, fuelled by British anti-semitism and sniffy elitist disdain for Arabs, states that “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

@cameronreilly has drawn our attention to Antoine Capet’s review of a new book examining the historical charade behind the manufacture of the Balfour Declaration. James Renton in “Zionist Masquerade: The Birth of the Anglo-Zionist Alliance 1914-1918” demonstrates that

the Anglo-Zionist alliance was built on spurious foundations, with false pretences and hidden agendas present at all stages in its inception and early development. His supporting evidence comes from the usual repositories in Britain, notably the National Archives (ex-PRO) and the Imperial War Museum, but also from Israel (Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem) and the United States (most prominently the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio). Renton uses American Jewish Archives, because it is one of the central premises of his undertaking that the initial moves on the part of the British governing elite were primarily designed to woo American Jewry.

Ironically, the author suggests, the Anglo-Zionist alliance was born of the deeply ingrained anti-Semitism of the British upper political establishment.

…

This fundamental distrust and rejection of the Jews on the part of the British promoters of the Anglo-Zionist alliance is the first element in the “masquerade.”

The second element is best made explicit by a quotation from the introduction: “The decision to issue the Balfour Declaration was not therefore driven by British strategic interests in the Ottoman Empire.

…

Renton very convincingly points to the third misapprehension by arguing that there was no real demand for a “Jewish home” among world Jewry, if only because there was no such thing as world Jewry.

The construction of Zionism as an artificial tradition, ideological motivator and propaganda is dissected.

Simultaneously, a parallel “invention of tradition” was taking place to counter the dominant position of the anti-Zionist Anglo-Jewish Association and Alliance israélite universelle, which clung to English and French as the language of instruction in their schools in Jerusalem. “One of the quintessential elements of the Zionist project was the invention of Hebrew culture,” which was given a tremendous boost by British authorities after their conquest of Jerusalem in December 1917, “essentially a propaganda measure” (pp. 106, 91). The Ministry of Information staged a “theatrical” reception for the official Zionist Commission headed by Weizmann in order “to create specific messages for Jewry,” especially the Jews of America, as the Bolshevik Revolution had greatly reduced communication with Russian Jews (p. 112). Here again, therefore, a two-way make-believe process was at work, with the British government using the Zionists for its own agenda and the Zionists using the British government for theirs. But, of course, at such games, one player always turns out to be cleverer than the other, and Renton has no doubt which it was: “the Zionists were undoubtedly used by the Government. They were not, however, unwitting pawns, duped by the British. It was in fact the Zionists themselves who established the rationale for using Zionism as a propaganda weapon, and consistently showed the Government how and why this should be done” (p. 7).

Avi Schlaim points out that it was the British who approached the Zionists – some analysts consider territorial strategic interest primarily dictated British actions.

On further reflection, however, the British felt that control over Palestine was necessary in order to keep France and Russia from the approaches to Egypt and the Suez Canal. In Vereté’s account, it was the desire to exclude France from Palestine, rather than sympathy for the Zionist cause, that prompted Britain to sponsor a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.

Schlaim highlights the basic injustice represented by the document –

The greatest contradiction lay in supporting, however vaguely, a right to national self-determination of a minority of the inhabitants of Palestine, while implicitly denying it to the majority. At the time that the proposed statement was under discussion in the War Cabinet, the population of Palestine was in the neighborhood of 670,000. Of these, the Jews numbered some 60,000. The Arabs thus constituted roughly 91 per cent of the population, while the Jews accounted for 9 per cent. The proviso that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine” implied that, in British eyes, the Arab majority had no political rights.

Part of the explanation for this peculiar phraseology is that the majority of the ministers did not recognize the Palestinians as a people with legitimate national aspirations, but viewed them as a backward, Oriental, inert mass. Arthur Balfour was typical of the Gentile Zionists in this respect. “Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad,” he wrote in 1922, is “of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.”[20] The most charitable explanation that may be offered for this curious claim is that in an age of colonialism everyone was in some sense implicated in its ideology. Balfour may appear today like an extreme example of the colonial mentality, but he was not untypical of his era.

The treacherous British owe Palestinian people their right to self-determination – yet, ironically, it is no longer primarily in their power to deliver.