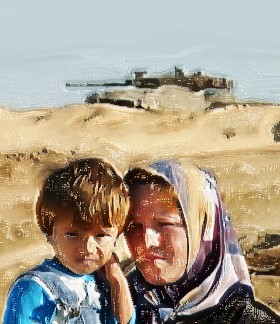

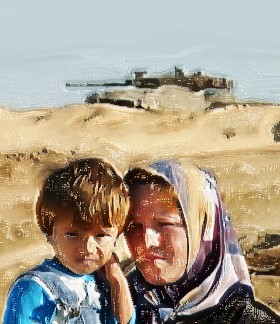

Leaves from the past swirl about my shattered country

Leaves from the past swirl about my shattered country

Phoenician glass cuts deep

within the wall to end all walls

My heart is occupied with grief of ages

Living when there is no hope

too hard to bear

the purple calling in my body is despair

my womanhood, logic and future denied

Oppressor and oppressed bound

and bloodied by hate

Like a beautiful, fragile tea set, the elegant device she’d made lay upon the table. Amirah scooped it up peremptorily, for it was deceptively sturdy, fastening the webbed belt about her body beneath her loose cotton blouse.

Plenty of time. Into her pocket she placed her folded poem, hoping to finish it on the bus during the interminable hot, angry checkpoint waits. The guards knew her well, they would smile lewdly at her and joke about her flashing dark eyes.

‘Amirah, princess of the territories, give us a kiss’, they would laugh, swaggering with their Utzis.

At first she ignored them, yet later, as her plan evolved, she would smile shyly in return, to build their trust. After months, they would not search her, even when all others were pried and poked when the enemy rampaged in revenge.

For three years following her degree’s completion, she had settled for a menial maid’s job in Tel Aviv, studying for her PhD in physics at night and weekends, her ticket to freedom – perhaps even to America. Then her mistress’s husband began to seek her out. One afternoon while the mistress was out with her rich, gossiping socialite friends, he had forced her to the bed and taken her. She had to trash the sheets and endure a scolding after she told her mistress she had burnt them whilst ironing.

And then, her uncle was captured, implicated in a tunnel building project to smuggle in food and medicine to the sanctioned, beleaguered city. The enemy had arrived at her parents’ home and bulldozed it whilst she scrubbed the enemy’s pots in the pretty modern villa by the glistening sea. Gone were her thesis notes and her computer, buried in the pitiful rubble of their lives. Her wise grandmother was nearly killed by the cruel, inexorable blades, hounded and taunted by the soldiers as she fled, hobbling down the street. The oppressors had everything except peace. Amirah wondered if they had ever really wanted it.

At university, Amirah had spoken against violence.

‘We are bound by violence, we are chained by it to them and we must break the cycle,’ she argued. ‘Resistance is legitimate under international law, yet violence will not work. They use it against us. Don’t you see?’

She had not despaired, although her brother still walked with crutches from the blows he received from the enemy when five years old. A stone he’d thrown at a tank missed and hit a soldier. With an education, she would be able to pay for him to walk again.

Nearly everyone had lost a relative, or knew of a house that had been crushed, sometimes with people still inside. The collective punishment was a brutal, never-ending scourge. What else was there to do but fight, to wear the enemy down with a despairing reaction to the oppression, to never let them know security whilst they denied it to others. Responsibility was never taken by the powerful and the weak were blamed for objecting to their punishment, justifying more delays for peace settlements, more land thievery for more enemy settlements and their hideous ghetto wall.

Amirah did not know whether the wall was to keep the horror in, or to keep it out. After her parents’ house was demolished and her future along with it, she too saw horror everywhere.

Amirah left her flat and caught the bus. The guards winked at her at the checkpoint.

‘How are your studies, Amirah?’ ‘When are you going to America, Amirah?’

Amirah smiled at them, her tears held captive by resolve. Today at the final checkpoint, it was a short wait, a miracle.

The ancient bus lurched its winding way to the leafy, well-to-do suburb by the sea. She walked to the plaza and sat on a bench. Amirah pretended to examine something in her satchel as she set the timer.

The ancient bus lurched its winding way to the leafy, well-to-do suburb by the sea. She walked to the plaza and sat on a bench. Amirah pretended to examine something in her satchel as she set the timer.

Within, she could feel the enemy’s baby move, and she gasped. From her pocket, she took the half-finished poem, scrutinising it carefully before screwing it into a ball and tossing it behind the bench. Tears threatened to erupt, and Amirah clenched her fists. Not long to wait now.

‘You dropped something’, a kindly voice spoke in the enemy’s guttural tongue.

‘It’s nothing,’ she replied, ;just a poem’.

‘May I read it?’ The interloper was a young pregnant woman in her late twenties or early thirties, with a guitar strung across one shoulder. She flattened the sheet and began to read.

‘It isn’t finished’.

‘I know,’ said Amirah. ‘I can’t think of an ending. It makes me too sad.’

‘It is very good, perhaps we can finish it together?’

‘But you are the enemy,’ Amirah whispered. Two minutes and there would be no more broken promises, no more fear and hurt.

‘I’m Danish, here to study archaeology.’ The woman smiled.

Amirah looked at her, saw unexpected warm eyes and her heart leapt.

Then she thought of her unfinished poem and in a blazing torrent, unannounced, the final words came.

Even in the silence of the desert

my soul knows no peace

it must walk this land forever,

free, yet within your reach

where you are not my enemy

and revenge is washed away

by joy.

Leaves from the past swirl about my shattered country

Leaves from the past swirl about my shattered country The ancient bus lurched its winding way to the leafy, well-to-do suburb by the sea. She walked to the plaza and sat on a bench. Amirah pretended to examine something in her satchel as she set the timer.

The ancient bus lurched its winding way to the leafy, well-to-do suburb by the sea. She walked to the plaza and sat on a bench. Amirah pretended to examine something in her satchel as she set the timer.